Anne Madden le Brocquy

"Come back soon!"Beckett in Conversation,"yet again" / Rencontres avec Beckett, "encore"

Edited by Angela Moorjani, Danièle de Ruyter, Sjef Houppermans

Brill | Rodopi. Leiden | Boston 2017Originally published as Volume 28, No.1 (2016) of Brill's journal Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui

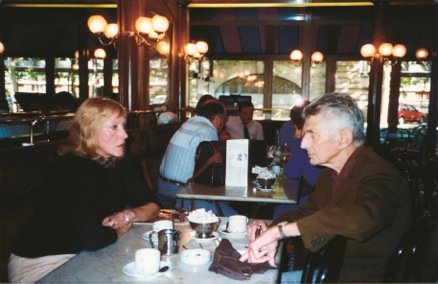

Anne Madden le Brocquy and Samuel beckett, Le Petit Café PML Saint-Jacques, Paris, 1988

Photo: Louis le Brocquy

When the painter Louis le Brocquy was a young man of twenty-three years he was introduced to the inside of a human head by a Dublin neurosurgeon who asked him to make a series of drawings of the pituitary gland and its surroundings while he was operating on a patient. Louis agreed to attempt this intricate work since he needed the five pounds he was offered for it. During the long hours of surgery he became more and more fascinated by the whole structure of the region behind the forehead, “the pituitary gland enthroned upon a bone pedestal over which the chiasma of the optic nerve floats like a canopy, and from behind the gland spring two white wings of bone,” as he described it.1 It was an unimaginable insight into the interior wonder of the human head and may well have been the beginning of Louis’s lifelong obsession with human consciousness, taking him through his encounter with the Melanesian and Polynesian decorated heads in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, the old Celtic-Ligurian cult of the head, which he came across in the museums of Provence and Ireland, the ancestral heads evoked in his paintings and hundreds of images of Yeats, Joyce, Lorca and Beckett (see figure 1). Speaking at Nice University, Louis said, “Like the Celts I tend to regard the head as this magic box containing the spirit. Enter that box, enter behind the billowing curtain of the face, and you have the whole landscape of the spirit” (qtd. in Peppiatt, 66).

Both poet and friend Jacques Dupin wrote of Louis’s head paintings (translated from the French by the poet John Ashbery):

A human head, an indistinct but familiar-looking face cautiously wears a hole in the canvas – and advances towards us. Its features are blurred, almost effaced, but the intensity of its presence keeps us riveted to its motion. It does not seem as though a painter had shaped this head; at most, he helped it to be born, forced it to disengage itself from the white shadow in which it lay buried. It is not defined by a contour, nor by the successive contributions of brush stroke and line. Rather the form, organically erected like a slow coagulation of space, seems to rise implicitly out of the suppression of everything that might be foreign to it. What it offers is not the appearance of a face but its inner construction, the facets and tensions of a being in the act of becoming.

(qtd. in Walker, 104)From the 1960s Louis and I were often in Paris seeing friends, their exhibitions as well as attending our own. Samuel Beckett’s friend since Trinity College Dublin days Con Leventhal was at the time his daily visitor in Paris, helping him with his papers and abundant mail. When we met him in 1978, Con knew of Louis’s 1965 painting of Beckett and was surprised that we were not in touch with him. “Contact Sam without fail,” Con urged us. The following morning a pneumatique arrived at our studio from Beckett inviting us to the PLM Hotel on boulevard Saint-Jacques. This was to be the first of many more meetings and the growth of a friendship between us ever closer as time went on, until Sam left this world eleven years later.

There was an immediate feeling of kinship between Sam and Louis: two Dubliners and a shared landscape: the Wicklow mountains, Dun Laoghaire pier, the sea and the salty air. James Joyce had his own microcosmic epiphany of Dublin and its surroundings and perhaps enabled Louis in his paintings of him to “grope for something of his own experience within the ever changing landscape of his face […] of that boat-shaped head, the raised poop of the forehead, the jutting bow of the jaw, within which Joyce made his heroic voyage, his navigatio” (209).

Louis saw landscape as an extension of ourselves: “a paradise […] becoming part of us was our central need, dying in to it and not merely disappearing” (265). In Waiting for Godot there is a hope and a longing, an open door in the mind, but nothing comes through the door, hope is never fulfilled and one expects never will be. Alone, alienated, not even sure of our identity, we search for something tangible. Landscape confirms existence in so far as it is remembered. The road to the mountains. Sam told us of the walks he had with his father as a boy taking them toward the Wicklow mountains that they could see in the distance, in the winter often capped with snow.

The majority of poets, writers, visual artists and musicians, who lived in the mainly Christian twentieth-century Europe, felt alone in face of the depths of human savagery and organised human slaughter in its wars, casting dark shadows over it. It was the case for Sam Beckett and Louis who were instructed in the two-thousand-year-old Christian tradition. Waiting for Godot makes this clear. Sam wouldn’t say yes and he wouldn’t say no to the question of religious content in the play. “The cross has so much symbolism, why not?” he said to me and chuckled when I asked him. The play leaves the question open, but even if Godot does not show up, the protagonists materialize as visible evidence in our post-real world. I believe that the possibility of independent survival of the spirit after death had been set aside by Sam, as it had by Louis early on in his life.

Sam told us his preferred play was Fin de partie; Godot seemed to “come to him” and was quickly written – as if he had very little to do with it – coming into his head as he and his wife Suzanne trudged south to Roussillon in October 1942 to flee the Gestapo. “There is a possible way out on the long road but where was it going, coming and going as it does? We are lost, above all we seek meaning,” he said speaking of Waiting for Godot and probably all of us, I think. This conundrum of ‘here and there’ depending on where you are is a core repetitive note playing through Sam’s work. Fin de partie makes it clear there is no dillydallying about getting out of the dustbins; you may get out but only to go back in again.

On several occasions Sam shared memories of the Joyce family. In June 1940, on leaving Paris temporarily during the exodus after Paris fell to the Germans, Sam and Suzanne stopped at the village of Saint-Gérand-le Puy, eleven kilometers from Vichy, to give a fleeting farewell to James Joyce, his wife and son Giorgio, who were holed up at Eugene and Maria Jolas’s school, while their daughter Lucia remained at a clinic in Brittany. It was obvious Sam was fond of Lucia from the sound of his voice when he spoke of her. He was persecuted by guilt feelings of all kinds and would put his head in his hands thinking about them. Sam held strong feelings for many friends, even one or two he called “scamps,” but the word ‘love’ was crossed out of his vocabulary. His bleak description of sex did not conjure much cheer there, but then I don't think Sam enjoyed an abundance of cheer in his life. He seemed to be on a particularly prickly rack of his making, plagued by possible failure in face of his absolute commitment to writing with the “no good, try again” voice gnawing at him.

On 15 September 1988 we were on a boat returning to France from Ireland. The front page of the Sunday Independent ran the final announcement by the Scott family to rescind the sale of James Joyce’s death mask, as very properly required by his grandson, and present the mask to the Joyce Tower. The article spoke of Louis’s crucial role in the outcome. The next evening we arrived in Paris. The telephone was ringing: it was Sam, to arrange a meeting the following morning at 11 a.m. in the PLM as usual. Inevitably we spoke of the resolution of the ‘Joyce scandal.’ Sam said we should all have our death masks made in our lifetime. He was eager for news, relieved to hear the outcome and felt Stephen Joyce should be satisfied. He told us that he himself had given two articles belonging to James Joyce to the Tower. One was an embroidered waistcoat, which Joyce’s son Giorgio had given him, and which had belonged to Joyce’s father, John Stanislaus. Joyce wore it every year on the day his father died, in an act of commemoration. Sam recounted that Joyce also gave a sum of money to a beggar or a very poor person on that day – “someone old and forsaken.” One year, after Joyce’s death, Giorgio asked him to perform the ritual. Sam found an old man in Montparnasse. Louis said, “I don't suppose you told him from whom it came.” Sam laughed, “No, no point: he would not have known who I was talking about” (238-39).

From time to time Sam would mention his family during our meetings. When, on our way to Dublin in March 1985, we gave him a record of Schubert impromptus played by Murray Perahia, he commented: “The only musical member of my family I know of, before my cousin John and my nephew Edward, was my father's mother. She lived with her husband in Waterloo Road in Dublin. She played one of those little organs, a harmonium, in the house and had a parrot that sat on her shoulder. When she kissed me or anyone else, the parrot used to peck her ear from jealousy.” He told us she disappeared at intervals, without telling anyone, for four or five days at a time. “I think she may have drunk a bit. Then she would reappear again. No-one said anything.” He went on to speak of his mother's mother. “She was a little woman, quite different. Very straight and Quakerish. There was no money because her husband put all he had into something and lost it. He drank and died, leaving her penniless, and she would often stay with my parents” (226).

One day I was with Sam he spoke to me of his dread of the dark at nightfall when he was young, and of his time as a student in Trinity College, when he walked the streets of Dublin through the nights in an attempt to confront this dread. Later on in his life what he called “tackling his dark” gave him some insight into these frightening states of being and eventual enlightenment. Sam knew of my despondence after my younger brother’s sudden death that had blocked my creativity. With his usual concern he urged me to “tackle my dark” more than once; “don’t be depressed, the dark is good material, it is it trying to be said,” Sam wrote to me shortly after our meeting in February 1987 (251). I think he believed it was crucial and might spark off some light as it had in his own case. And for some time when we met he would enquire, “are you tackling your dark?” I had told Sam of the eighty-two crowded notebooks I found after my brother Jeremy’s death showing the depths and breadth of his enquiry into what he called “the language of gesture and movement” in mime, dance and silent film, as well as two essays, “The Comic Figure” and “The No Word Image.” He dwells on Eisenstein, Meyerhold, Oskar Schlemmer, Antonin Artaud, Peter Brook and Beckett, and reflects on a number of other filmmakers and silent-film actors. Richard Kearney, who holds the Charles B. Seelig Chair of Philosophy at Boston College, edited the material bringing it together as a single thesis called The No Word Image by Jeremy Madden-Simpson. After the book appeared in 1987, I sent a copy to Sam and his reaction was immediate: “an interesting book,” he wrote in a letter to me and repeated it the time we saw him on 12 September 1987.

Sam always asked us about our work first thing when we met and when we left him always bade us “come back soon!” When we came to Paris he was the first to leave a message on the phone, which sounded as if he was calling from outer space: “Sam here. See you tomorrow. Same time. Same place.”

In an interview with David Sylvester, the painter Francis Bacon says: “I think that if one could find a valid myth today […] it would be tremendously helpful. But when you are outside a tradition, as every artist is today, one can only want to record one’s own feelings about certain situations as closely to one’s own nervous system as one possibly can” (89). Bacon described his psyche as being dominated by a kind of “exhilarating despair” (89). Sam had reservations about Bacon. He felt he wallowed in violence. When I asked him at our meeting on 12 September 1987 if violence wasn’t at the core of our humanity, Sam replied that he felt it was frailty, an incapacity to cope with living that was the base. Sam’s anguish seemed to be more about the impossibility of writing, cut off and alone with “the dream of giving form to the ruin of the mind.” He seemed to be caught in a mental labyrinth and not optimistic about finding a way out: “The task at hand is impossible.” He appeared grey in the face thinking about it, as well as the worrying productions of Godot coming up in New York and London at the time, though he felt the Lincoln Center production had more chance: “I’m too tired, I give up. I can’t keep track of them.” And then there were times Sam seemed almost happy, as he talked about the making of the Stuttgart TV film, What Where, which had interested him very much, and he hoped to go back to do more filming using close-ups to scrutinise the face on film. He was also pleased and relieved when Madeleine Renaud and Jean-Louis Barrault told him Oh les beaux jours (Happy Days) at the Rimini Festival that year was a triumph.

Sam’s anxiety about the various productions of his plays prompted me to suggest to him, “Sam, what about a production of Waiting for Godot at the Gate Theatre in Dublin with Irish actors and a set by Louis?” He looked at me steadily with his piercing blue eyes for a few seconds. Then, “I would be very happy if this were to happen,” pause, “the Irish voice is important.” (As we know he had written Krapp’s Last Tape for Patrick Magee after hearing the sound of his voice.) Then and there he gave me the go ahead to contact Michael Colgan, the flamboyant director of the Gate Theatre, who was excited by my news, and joked, “you should have been a producer!” From then on Louis and I became involved with the production all the way to the first night. Sam had made clear to me his wish for Walter Asmus to direct the play which I passed on to Colgan.

We saw Beckett frequently the first part of 1988 to discuss plans for the Gate Theatre production. He was very thin that winter after an illness and wore a little woolen cap that he would pull off, and his hair, en brosse, sprang up and he looked more himself again. At a later meeting, in June 1988, Sam was indignant about news in the International Herald Tribune that he was directing three of his plays for video. It was all lies he said. There was a weary defiance throughout and he left earlier than usual making for the door, then returning to us and taking hold of both our arms saying “in Endgame Clov says ‘when I fall I’ll weep for happiness,’ and as I go out I say, ‘if I fall do not pick me up.’” We gave him no such promise. Sam had let it be known that Hamm and Clov might be partly himself and his wife Suzanne, which made it all the more shocking. Again he seemed distraught about two other productions of Godot in different parts of the world.

In the meanwhile, Godot at the Gate had taken off. There were many discussions about the actors and their roles before finally deciding on Barry McGovern, Tom Hickey, Stephen Brennan and Alan Stanford. Sam spoke to Louis at length about the play and the set. The mound / stone and the tree should be rigorously simple, he emphasised. He spoke also of the diagonals in the respective positions of the tree, stone and actors: “Walter knows all this.” He insisted as always on reduction and simplicity. He made little sketches on the back of one of our bistro bills indicating their nature and significance in the play, as well as of the tree on the top of the front page of the Libération newspaper. We understood that Vladimir’s querencia was the tree, upward reaching into the air; Estragon earthbound, his querencia, the stone; Pozzo very unsure of himself, “a bluffer and blusterer, who overcompensated.” There was a symbiosis between him and Lucky; and a symbiosis between “long thin Didi and short fat Gogo.”

Louis’s conception of the scribbles he made on the costumes was of a “formalised cobweb,” which extended to the flats, flies and headers forming a conceived space intended to be barely perceptible on the outskirts of a centre-lit stage. Louis had insisted on painting them himself as well as the costumes for the actors, working on these in the area of the Five Lamps district of Dublin for days and nights until his arms felt like a rag doll’s. We attended many rehearsals,

Walter Asmus sometimes shouting at the actors or ordering absolute silence from us watching from the front stalls. Our involvement with the play and players grew more and more intense until the opening night on 30 August 1988, when we held our breath, and a dizzy excitement ran through me during the play. After the show there was champagne, hugs and congratulations to the actors from us and their friends in the dressing rooms. And eventually they came with Michael Colgan and Walter Asmus for a late supper at the house to celebrate a great performance of a great play.

As his messengers we hurried back to Paris to relate the triumphant event to Sam. “Tell me all, leave nothing out,” were his orders given with warm embraces. When asked I told him I was incapable of relating the event fully and fairly because it had been such an intense and emotional involvement, to which came the sharp riposte “you’re the one person who should be able to tell.”

Later on that morning I recounted the dream I had the previous night about Shakespeare, who was interested in Pozzo’s line in act 2 ending with, “they give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.” In the dream I ask Sam to recite to the bard Vladimir and Estragon’s beautiful exchange:ESTRAGON. All the dead voices.

VLADIMIR. They make a noise like wings.

ESTRAGON. Like leaves.

VLADIRMIR. Like sand.

ESTRAGON. Like leaves.His au revoir “come back soon!” accompanied us, as we left him standing on the boulevard Saint-Jacques outside the PLM.

Following this visit, long talks on the telephone ensued from our home in the south of France, and Sam sounded stronger and in better form but said he forgot everything: “the ruin of the mind.” Jérôme Lindon had reported his mind to be in perfect order. I think Sam was uplifted by Godot at The Gate, by the public response and by the full houses with so many young people coming to them as well as the many messages from friends about the production. Michael Colgan’s future plans to produce all his plays for theatre, radio or film in a world-wide event was an exciting project for Sam to contemplate.

The birth of Waiting for Godot at the Gate had taken place and now the production would grow and change. Unfortunately the costumes Louis painted “disappeared” and couldn’t be found according to Michael Colgan, but some of the drawings he made are illustrated in the programme for which Michael had asked me to write an introduction. This adventure had in some way brought our friendship to Sam even closer. The last year of his life, we saw him several times in his sparse little room at Tiers Temps, the Home he stayed in after a bad fall in the summer of 1988. We came with a bottle of Bushmills whiskey one September evening of 1989, as he had run out, which caused his response “no beating about the bush with you two.” “It helps,” he murmured, as he poured the whiskey into three little glasses. From his chair Sam set out to fetch the water from the fridge, both a ritual manoeuvre and a trial. “How will I get back?” He accepted no helping arm; it had to be accomplished alone. Sam was so thin and frail we wondered if he would get through the winter which he faced with dread. We left him feeding sparrows with crumbs outside his room on the path where there was a little green wooded patch and he called to us, “come back soon!”

Louis had enquired about Sam’s work: “No, nothing, nothing left.” He had translated Stirrings Still into French, and it would be published by Les Éditions de Minuit in November. He had also translated “Comment dire” into English. The last line, which in French is “comment dire,” in English has the much more ambiguous ending, “what is the word,” ‘what’being the possible answer. There is no question mark. He said these ambiguities were possible in English but did not exist in the French version. We talked of the Gate Theatre and then of the Abbey which was in trouble. Sam and Louis concluded it had always been in trouble: “Remember when Yeats rejected The Silver Tassie?” Sam said bitterly, “it drove Sean [O’Casey] out of Dublin forever.”

Sam’s doctor had driven him a month earlier to see his cottage at Ussy on the Marne. Visibly moved, he recounted how he found it on that summer day up there alone on the hill, the countryside all around and no one to be seen: “I never realized how beautiful it was until I lost it.” He declared he would never return there, and of his writing he murmured again, “nothing, nothing left. It can’t go on much longer.”

We would see him one more time at the end of November. There were various things Sam wanted to discuss. He gave us Soubresauts, the translation of Stirrings Still, with Louis’s two drawings of Sam that he had made during the past six months. “Why Soubresauts, I don’t know,” he admitted, but as Louis said, he was forever leaping beyond himself. Sam wanted to discuss the Great Book of Ireland for which he had selected two possible poems, both early works from the collection Echo’s Bones, one of six lines, “The Vulture,” one of four, “Da tagte es.” He recited them to us and asked Louis to choose one. He chose the latter. On the parchment page Sam would later write the poem beginning with “redeem the surrogate goodbyes.” Referring to the line “the sheet a stream in your hand” Sam said, “The stream of the sheet held in her hand, the sail of the boat going out to sea, but also the bed sheet, the winding sheet.” After an hour Sam suddenly tired. We hugged each other close and long. He was all bones. We left him in the unadorned silence, his penetrating gaze upon us.Three weeks later Sam died on the 22nd of December.

Sam was a heroic stoic. Many of his characters were invested with this stoicism and dignity in face of the tragic, as well as with his acute sense of the absurd, of the comic nature of things. From his interior isolation Beckett voyaged with enduring courage into the uncharted seas of his art. We perceived in him not only a great artist but an extraordinary human being engaged in his work with an unflinching scrutiny of existence. The significance for Louis of Sam Beckett’s head increased with the deepening of their relationship. In the many images he painted of him after his death, he was further moved by his own evocations of Sam but felt they could never reach the hidden depths of the man. 2

Notes1. Quoted in Le Brocquy, 46. In the rest of the article, all parenthetical page numbers, without a preceding name, refer to quotations from the same book on Louis le Brocquy.

2. Photo: Anne Madden le Brocquy and Samuel Beckett, Le Petit Café PML Saint-Jacques, Paris, 1988. Photo: Louis le Brocquy.

Works Cited

Beckett, Samuel, Stirring Still, ill. Louis le Brocquy (New York: Blue Moon; London: Calder, 1988).

Le Brocquy, Anne Madden, Louis le Brocquy: A Painter Seeing His Way (Dublin: Gill, 1994).

Madden-Simpson, Jeremy, The No Word Image, ed. Richard Kearney (Dublin: Eason and Son, 1987).

Peppiatt, Michael, “Interview with Louis le Brocquy,” [cover story], in Art International 23.7 (1979), 60-66.

Walker, Dorothy, Louis le Brocquy (Dublin: Ward River, 1981).