exhibition programme | paintings | tapestries | prints | chronology of a life | market | biography & bibliography | agents | news | contact

Tapestry design

biographical note | exhibitions & catalogues | public collections | books illustrated | dated biography | group exhibitions | theatre | monographs | articles / film / radio

In 1948 , Edinburgh Tapestry Weavers, an ancient industry under the patronage of the then Marquis of Bute, invited a number of painters, working in London, to design tapestries. The artists included Stanley Spencer, Jankel Adler, Graham Sutherland and Louis le Brocquy, who later continued his work in this medium in collaboration with the Tabard workshop at Aubusson in France. His first tapestry continued his preoccupation with the travelling people: Travellers 1948 was exhibited originally by the Arts Council in London in 1950. It depicts a woman and a young child with an old faun-like figure of a man: the delineation of the figures is strongly influenced by Picasso but the weaving of the tapestry with its overall surface of leaves and shadow patterns is much indebted to Lurçat, so that an intriguing cross fertilisation of Picasso/Lurçat here takes place in the forms of an Irish travelling family. The second is one of le Brocquy's best known tapestries, Garlanded Goat of 1949/50 (1). The goat is the embodiment of the pagan, leering king Puck, hero of the ancient Puck Fair at Killorglin, Co. Kerry. The London critic, Robert Melville, has written of it: "Apart from a few of Lurçat's, it is the most successful tapestry I have seen and a superblatter-day example of the Celtic art of surface decoration."

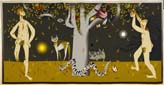

(NB: Other than in reproduction, Dorothy Walker omits to mention Allegory, the artist's third tapestry design following Travellers 1948 and Garlanded Goat 1949-50, it is contemporary with A Family, but the theme is treated with colourful gaiety and with a monumentality surprising in its modest dimensions. A relationship may be perceived between the paintings of this period and this tapestry, not evidently in colour or mood, but clearly in drawing and in its characteristic planes. Allegorical allusions appear to include a sun, a moon, the winding of a skein of vermilion wool and the emergence of the child).In 1951, Mrs. S.H. Stead-Ellis, whose art collection already included le Brocquy tapestries, commissioned three related tapestries, adaptable as screen, rug and firescreen, on the theme of the Garden of Eden- Adam and Eve in the Garden, Eden and Cherub. He treated the theme with archetypal imagery in a classical, even traditional manner, the sun and the moon appearing respectively in the male and female spheres. The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil appears as in traditional French mediaeval tapestry with the birds and butterflies among its leaves, but he adds a surrealist aspect with eyes as well as leaves (as befits a tree of knowledge) and fish swimming in its branches. In he style of drawing, the tapestry corresponds closely to the paintings of the period, particularly the figure of the man, which is closely related to Man Writing. Le Brocquy has written with real insight on the design of tapestry in his 1956 essay on Lurçat:

In tapestry this conceptual vision has been given form by Jean Lurçat in his own highly particular display of age-old symbols. Here, on an unfolding surface, the sun and his herald, the cock, once more proclaim with pagan fervour the potency of natural life, while man and dog alike are in life, in death, related to the leaves. Related to the leaves: to Lurçat relation is paramount. His individual expression of it is perhaps the most personal of his great contributions to contemporary tapestry. Sitting in my London studio recently he enlarged on this theme, carefully discovering the small, golden reflections and broken shadows which his glass of whiskey cast around it. Books, table, papers, trouser leg, even the rush matting on the floor, were decorated by its presence, proclaiming for him the woven interdependence of all things. This, his central conviction, Lurçat has extended to the analysis of his medium. His rejection of the painted cartoon in favour of a full-scale linear cartoon, directly indicating each woven transition of colour and tone; his selection of a simple range or gamme, of standardised and numbered wools on his cartoon by means of their numbers; his choice of coarse and lively wools; his re-introduction of the visibly large Warp; all of these technical decisions sprang from a passionate belief in the wholeness of concept and execution. In this belief Lurçat was supported by his own insight into the nature of tapestry and his study of the practice and works of mediaeval French designers and weavers, superseded but never surpassed.

Lurçat's method of designing, already widely practised in France, has given new life to French tapestry, now more joyous and frank, more durable and economic than at any time since the end of the 16th century, when resistance to Renaissance idiom finally collapsed. His reconstituted technique imposes no particular style on the designer, as may be seen by comparing the quantity of stylistically varied work recently produced at Aubusson. It is essentially a return to mediaeval ways. In one form or another it represents the only practical and economic way of producing "a very large work of woven and coloured wools": a tapestry. For any designer who has made a cartoon by this direct method of Lurçat and by the indirect, copy-a-painting method of, shall we say, Boucher, there can be no remaining doubt in eye or in mind as to the superiority of the former when comparing the two resultant tapestries. Only those can remain obdurate who insist on the virtue of cleverly and laboriously translating paint scumbles into weft.

Eden remains one of le Brocquy's most interesting works; the vibrant colourful design is based on a series of subdivisions of the classical Golden Section, yet the design bleeds off the tapestry in most unclassical manner. The Woman's Heel which the angel promised would crush the serpent descends from above, while the serpent continues to writhe below. The leaves of the Tree mingle with the tears of Adam and Eve while the fatal apple is discarded, bitten and segmented. The angel of the Cherubim in the the smallest work is an ambiguous figure suggesting apocalyptic disaster rather than heavenly glory, carrying in its palms a prophetic stigmata. But the beautiful rose-pink colour of the angelic figure does suggest some heavenly background. The artist, in an interview with Harriet Cooke published in The Irish Times on May 1973, describes his involvement with tapestry as something he had "rather stumbled into by accident". But after that first commission from Edinburgh Weavers, the medium took on its own distinct fascination:

I always found it a kind of recreation, involving completely different problems, it is refreshing in the sense that one is exhausted in a different way. There is also another aspect of it which is very exciting to the painter, who has this struggle with the angle, and that is the same aspect which is so exciting, say, to the Japanese Satsuma potter, when he puts his jar in the oven and waits on tenterhooks for it to come out.It always comes out a little different from what he had imagined and sometimes he has wonderful surprises. The method I use is a system of notation, a linear design which is numbered in the colours of a range of wools. Although one can visualise what one is doing, to a certain extent, when the tapestry is palpably there this causes an independent birth of something, and that is so contrary to the whole involved process of painting that it is rather refreshing.

The final work of these early tapestries, Sol y sombra, marks a watershed in the artist's career which came about as a result of his interest in design. Le Brocquy had become quite successful as an industrial and graphic designer, designing symbols, packaging, and textiles, the earliest of which were based on the megalithic carvings in Newgrange, Co. Meath. In 1954, he was appointed Visiting Tutor to the Textile School of the Royal College of Art, London, and in 1954/55 he and the Irish architect Michael Scott set up a design agency, Signa Ltd., based both in Dublin and in London, to promote industrial design in Ireland and England... In 1955, the British export magazine, Ambassador, sent le Brocquy to Spain to make an extensive tour and to draw from all over the country free visual impressions, which would subsequently be adapted and used by textile firms for curtain materials. The trip was indeed immensely successful; the Gimpel Gallery held an impressive exhibition of the resulting sketches and three British textile firms issued dozens of le Brocquy designs. That immediate result, however, was nothing compared to the profound effect on the artist's painting. The Spanish light literally turned his world inside out. Shadows became more real than substance, hot colours entered the shade, and cool colours the heat; matter dissolved in the blinding white light.

The Táin (1969) was illustrated by le Brocquy in a proliferation of superb black brush drawings which he modestly described as "shadows thrown by the text"... Such an impact was made by the Táin drawings in Kinsella's book that le Brocquy made a series of lithographs in a larger scale of key images from the book. The drawings transferred with ease to the larger size, while retaining their spontaneous character of brush drawings in Black ink. A vivid immediacy of movement was the essence of these single images. The theme of the Táin gave rise to a fresh surge of creative activity in the realm of tapestry, completely different from the earlier series. The first Tain tapestry was commissioned by the architects Scott Tallon Walker for P.J. Carroll & C.'s cigarette factory in Dundalk, Co. Louth. While the subject of the Tain may not immediately relate to cigarettes, the location of the factory is close to the legendary action of the epic, so that the artist chose the theme to relate the local mythology. The Táin, which is an Irish word meaning "hosting" or gathering of a large crowd for a raid, gave the theme of the tapestry. It is a very large work (407 x 610 cms) with its surface completely covered in multi-coloured heads, all facing the spectator. These heads retain that relentless individuality of single beings having no relationship to their neighbour; lacking Roman order, there are no military ranks, no imposed external form, the mass of heads is held together by an inner, inherent order, like a flock of plover. "In this tapestry", le Brocquy has said, "I have tried to produce a sort of group or mass emergence of human presence, features uncertain - merely shadowed blobs or patches - but vaguely analogous perhaps in terms of woven colour to the weathered, enduring stone boss-heads of Clonfert or Entremont - or of Dysert O'Dea... This poses a difficult pictorial problem. Pictorially a mass of individuals, conscious of each other, implies incident - better left to photography perhaps. In Clonfert each individual head is conscious only of the viewer vertically facing it. This I think is the secret of their mass regard. Each head is self-contained, finally a lump of presence. No exchange or incident takes place between their multiplied features." In an interview for Hibernia in 1970, I asked him whether he had been undaunted at the thought of treating this very large architectural surface with such a fragmented image. He replied: " A work like this certainly implies a big claim on other people, a big responsibility. I am very aware of this, but I was not nervous of the fragmented or multiple image. On the contrary, it was this image which encouraged me by suggesting a way in which the head-unit might be transformed into a vast honeycomb or mosaic, giving some kind of cohesion or vibration to the architectural surface."

Following the large Carroll's tapestry, le Brocquy designed a series of six smaller Táin tapestries with similar patterns of irregular oval heads; the minute,

irregular "features" of the faces, even on this tiny scale, assert the individuality of the members of the crowd. One of the tapestries, Men of Connacht, composed of rows of black heads casting a grey shadow behind them, achieves an effect like the traditional "lace" stone-wall of Connemara. It recalls the legend of a king who shared the Celtic identification of the stone boss with the head, to the extent of attacking a stone wall under the illusion (admittedly cast buy a spell) that he was dealing with upstanding warriors. All of the Táin tapestries were woven in Aubusson, and in them the artist has contrived a masterly conjunction between the narrative content of the epic, his own and the ancient Celtic concern of the head image and the visual and architectural demands of a large modern wall-hanging. Le Brocquy has designed only two tapestries for the V'soske Joyce hand-looms at Oughterard, Co. Galway, which have made many tapestries for the other Irish artists. The first, made in the early sixties, is quite unusual for le Brocquy but does take advantage of the relief possibilities inherent in the arbitrarily cropped surface of the wool. It is based on his painting of a procession of girls carrying lilies, with a white linear outline depicting the figures of girls recessed into the rich blue surface of the tapestry. This work is very close to his early St. Brendan the Navigator, made for the same firm P.J. Carroll & Co., which also used a white narrative line on a tobacco-brown ground for the legend of Saint Brendan's sixth-century voyage across the North Atlantic.

Dorothy Walker

NOTE: (The other works relating to the Táin are: Cuchulainn I 1973, Cuchulainn II 1973, Cuchulainn III 1973, Cuchulainn IV 1973, Cuchulainn V 1973, Cuchulainn VI 1977. In 1999 the artist has added to this series three further designs: Cuchulainn VII, Cuchulainn VIII, Cuchulainn IX.)