exhibition programme | paintings | tapestries | prints | chronology of a life | market | biography & bibliography | agents | contact

One man's eye:

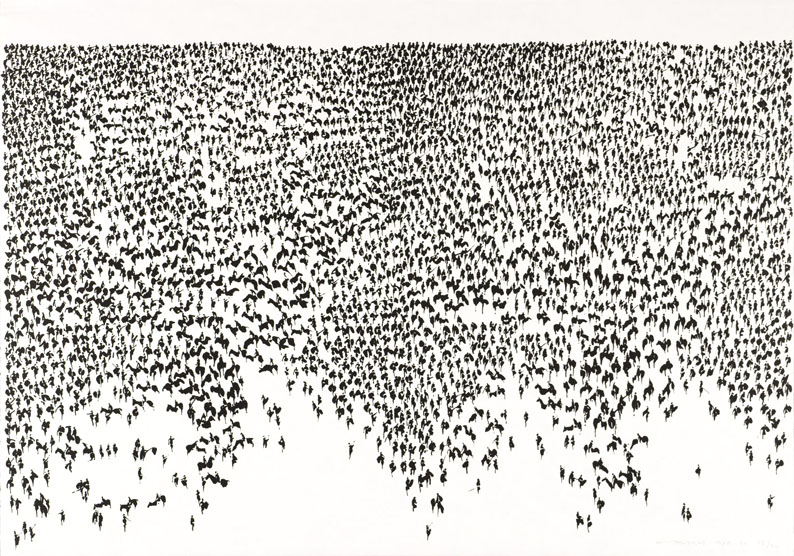

Dr. Yvonne Scott. The Táin. Army massing, 1969

Army massing, 196

lithograph on Swiftbrook paper, 38 x 54 cm. Limited edition of 70 proofs plus 1 artist's proofThis was my first introduction to Louis' work, when I was in my early twenties. I bought a copy of Thomas Kinsella’s translation of The Táin in Parson's bookshop at Baggot St. bridge, and I still have it. I was spellbound by the images, but Army Massing in particular, and it still has the same impact on me.

…

The dense fog you saw filling the hollows, that was the breath of those fierce

men filling the valley until the hills between looked like islands in a lake.

[The Táin, trans. Thomas Kinsella]

This scene is observed as though from a high viewpoint: the magisterial view, it appears, of the commander taking stock of the great hoards of mounted warriors massing below. It is a scene to instil satisfaction, pride, awe and anticipation. Here is a cause for which armies of thousands were prepared to answer the rallying call, and for which to die if necessary. Then, as now, the cause was one of tribal pride, the symbols of power, and of access to natural resources (the legendary fertile bull).

Army Massing is one of a series of black and white images designed by Louis le Brocquy to accompany Thomas Kinsella’s translation in the 1960s of The Táin Bó Cuailgne, an ancient epic prose text that forms the centrepiece of the Ulster heroic stories. Le Brocquy describes his graphics, poetically, as ‘shadows thrown by the text’ suggesting the images taking shape in the imagination as one reads.

In this scene, the panorama is filled with the massing army whose extent and density carpets the landscape, obscuring both its details and its limits. The swarm extends beyond the edges of the picture space, rolling out beyond the horizon whose line is inferred by the regiments of men. Such magisterial vantage points, it has been proposed, provide a generalised view, blurring the particular or individual. Le Brocquy, however, contradicts this perception in an image that is composed entirely of distinguishable parts: the flow of figures that provides the texture of the landscape is made up of hundreds of differentiated characters. While they are not recognisable personalities, their separate humanity is established. They read like the stitches of a tapestry: singular but crucial to the whole, remove one and the entire is bound to unravel. The figures are suggestive of oriental aesthetics, each represented with a calligraphic gesture. The limit of colour to black and white is intended to emulate the type-set page – texture as text – with the narrative’s characters about to assemble into their lines like sentences.

Le Brocquy intended this graphic series to be impersonal, as befitting an ancient and distant legend. However, one is drawn into the drama of the anticipated event.

In its tragedy of misguided heroics, flimsy justification, predictable outcome, and dispensable humanity, it could just as well be a contemporary scene, hence its continued relevance and pathos

Dr Yvonne Scott. B.B.S, M.A., Ph.D, Dip. H.E.P.

Director, the Irish Art Research Centre (triarc) and lecturer in the History of Art, Trinity College Dublin.