Moves studio, converted garage, Hollyberry House, 'The Watch House',

Holly Hill, Hampstead (Spring 1950). Embarks on the 'Grey Period' Family paintings (c.1951-54), the third distinctive period in the artist's work.

According to John Russell: 'In the early 1950's, above all, he came before

us as a man who was looking for the image that would compound all other

images. Anyone who was around at the time and concerned with what was called"post-war

British art" will remember the painting called "A Family"

(1951; National Gallery, Ireland).'91 Widely acknowledged as the artist's

masterpiece from the period, the painting marks a shift in palette from

the comparatively colourful work of the late forties topredominant whites

and greys. John Berger writes in Art News and Review: 'His style

has developed and changed; his colours are pale and severe - the Family is mostly grey; his forms, in their movement both across and into the picture,

are precise. This finesse implies - because le Brocquy's motive is always

human - a tenderness which is not sentimental, and a sense of wonder which

is exact; one thinks twice aboutthe quite ordinary but in fact miraculous

construction of any man's back, having looked at the father in the Family.

Le Brocquy is completely free of contemporary tendency to cosmic megalomania.

It has become pretentious to talk of an artist's humility, yet that is

what distinguishes his work; his studies testify to his patience, and his

final, large picture to his refusal to evade simple but difficult problems

by relying on the grandiose cliché.'92 Dr. Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch

notes of this large composition:'An oil on canvas, almost two metres wide

the picture depicts a family group ... The mother, lying on a table, leaning

on one arm, stares out with quiet dignity while a menacing looking cat

peers out from beneath the drawn sheet. In the background the father sits,

head bowed, in a pose suggesting total dejection. He appears to be oblivious to the

small child holding a bunch of flowers; a symbol of hope. The three sombrely

painted figures inhabit a grey concrete bunker, lit by a bare bulb. The

theme of this disturbingly bleak work is the nature of individual isolation

and the breakdown of societal norms.'93 Conceived in the wake of World

War II, the artist explains: 'I have always been fascinated by the horizontal

monumentality of traditional Odalisque painting, the reclining woman depicted

voluptuously by one Master after another throughout the history of European

art - Titians' Venus of Urbino, Velasquez' Roqueby Venus turning her back on the Spanish Court, Goya's Maja clothed and unclothed,

Ingres' Reclining Odalisque in her seraglio and finally the great Olympia of Edouard Manet celebrating his favourite model, Victorine

Meurent. My own painting A Family was conceived in 1950 in very

different circumstances in face of the atomic threat, social upheaval and

refugees of World War II and its aftermath. The elements in its composition

correspond in some ways to those of Olympia, if not to Manet's cool

sensuality. The female figure in A Family may be seen to take on

a very different significance. The man, replacing Manet's black servant

with bouquet, sits alone. The bouquet

is reduced to a mere wisp held by a child.The Olympian black cat in turn

becomes white, ominously emerging from the sheets. This is how A Family appears to me today. Fifty years ago it was painted while contemplating

a human condition stripped back to Palaeolithic circumstance under electric

light bulbs.'94 The painting will prompt John Berger to declare in The

New Statesman: 'The right-hand half of the very large Family group is, by itself, the finest bit of contemporary painting I have seen

for a long time, and I am now convinced that le Brocquy is one of the really

promising (in this case that infuriating word is not an excuse but an achievement)

British [sic] painters of his generation.'95 Paints Indoors Outdoors (1951), Bathers (1951; Dept. Forign Affairs, Dublin), Child with

Flowers (1951), Man Writing (1951), Man with Towel (1951), Woman in White (1951). According to Alistair Smith: 'The key painting

of the group is entitled A Sickness (1951) which may owe something

to the composition of early works by Munch, where, very often, a figure

broods in the foreground over what is happening behind. Here we are witness

to two women, one seated and caring, the other near death, floating within

sheets. In the other pictures of the grey series, the mood is of pervading

melancholy. Despite the persistent quotation of elements from Picasso's

Pink Period - the bouquets of flowers, the sparse interiors and the similar "intervals"

between the figures - there is nothing of the sweetness of that part of

Picasso's oeuvre. Le Brocquy has moved from a perception of his Irish travellers

as outcasts, who thereby possessed a preternatural vitality, to an understanding

of dismal entrapped, post-war urban society, refugees included.'96 Tapestry

design takes on a distinct attractiveness for an artist whose palette has

become essentially confined. The medium offers an unbounded outlet to le

Brocquy's feelings for colour. He explains: 'I always found it a kind of

recreation, involving completely different problems. The method I use is

a system of notation, a linear design which is numbered in the colours

of a range of wools. Although one can visualise what one is doing, to a

certain extent, when the tapestry is palpably there this causes an independent

birth of something - a surprise - and that is so contrary to the whole

involved process of painting that it is rather refreshing.'97 Designs three

related tapestries commissioned by Mrs S. H. Stead-Ellis, adapted as screen,

rug, and fire screen. Woven by Golden Targe Studio, Edinburgh, the series

includes Cherub (1951), recalling the 'Apocalyptic' paintings of

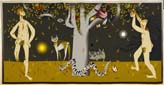

1948; Eden (1951), based on a series of subdivisions of the Golden

Mean, and Adam and Even in the Garden (1951), stylistically analogous

to his 'Grey Period' painting Man Writing (1951). Refered to as

the 'Eden Tapestries', the companion-piece Adam and Even in the Garden is adapted as a single piece with the three divisions of the Stead-Ellis

screen now pictorially replaced with the vertical inscriptions And the

eyes - of them both - were opened. The choice of subject-matter is

reflective rather than religious. Conceived allegorically, the artist explains:

'I chose as the theme for these tapestries the astonishing legend of Adam

and Eve in the garden of Nature, of the awakening of human consciousness,

the birth of the mind.'98 Designs six further tapestries for Chippendale

chairs commissioned by Edward Rice, Oak, Sycamore, Horse Chestnut, Lime,

Beech, Ash, woven by Edinburgh Tapestry Co. (1951). Exhibition at Gimpel

Fils, London (June 1951): Drawings, Watercolours, Oils & Tapestries, thirty seven works, including Two Rooms (1951), Indoors-Outdoors (1951) A Family (1951). Eric Newton writes in The Listener:

'Louis le Brocquy is a haunted artist. It would be easy to praise the pale

delicacy of his colour and the angular simplicity of his line. But plenty

of contemporary painters have precisely those gifts - they threaten to

become rather tiresome cliché - yet cannot use them for any expressive

purpose. Le Brocquy breaths life into the modish idiom. The familiar tricks

become vehicles of a powerful vision. The recumbent woman,

the back view of a man, the small child holding a nosegay of flowers who

recur as a leitmotif in more than half the exhibits at Gimpel

Fils, are the raw material for a kind of sonnet in paint, polished and

rearranged and played with until it appears in at least eight different

disguises ... Le Brocquy's exhibition establishes him as a lyrical artist

with an exceptional evocative gift.'99 Represented in Sixty Paintings

for '51, Arts Council, Festival of Britain, London (July 1951), Les

Tendances d'Avant-Garde dans la Peinture Britanique, Brussels, Belgium

(July 1951), le Brocquy prepares for his first gallery exhibion in Ireland

at the Victor Waddington Galleries, Dublin (December 1951): Paintings

and Tapestries, including Negro Woman in White (1951), Child

with Doll (1951). John Ryan writes in the Dublin Evening Mail:

'Louis le Brocquy discovered his peculiarly individual mode of expression

early in his career and courageously employed it even when doing so meant

that he had to discard a style which promised a fashionable and lucrative

future as a portrait painter in the traditional manner. That pedestrian

opinion has not forgiven him for this revolt against its standards was

amply proved by the deplorable attack on the painter inthe Evening Herald recently. Le Brocquy's stand and his subsequent development as an artist,

however, won him the admiration and respect of intelligent opinion wherever

his work has been shown. In great Britain he is accepted as one of the

handful of really brilliant painters of this generation, while America

in so far as she has had the opportunity to judge has reacted similarly.

Despite the strictures of the Evening Herald it is satisfactory

to note that the exhibition itself has been an outstanding success in every

respect.'100 In February 1952, A Family will elicit much debate

when a group of art patrons offer to present the painting to the Dublin

Municipal Gallery100b. The gift is rejected by the Art Advisory Committee at

the behest of Sean Keating on the grounds of incompetence. The Dublin Corporation

members are in the affirmative minority. The decision sparks widespread

controversy and extensive media coverage. Ineffectual protests are led

by fellow artists in the IELA Committee, within a small dynamic group supporting

contemporary art. The event mobilises modern art haters. Open hostility

is aired in letters sent to the press. Viewed as an 'unwholesome and satanic

distortion of natural beauty'101, and 'bewildering and repulsive'102, the

aversion is summed up in the following opinion published by the Dublin

Evening Mail: 'There is a place for monstrosities in the College of

Surgeons - there are plenty there - and it would give me much pleasure

to find a place for things like "The Family" ... It is not given

to man to see into the future, but I am quite certain that in another 100

years the works of Turner, Constable, and a Galaxy of true artists, whose

work is still with us, will be cherished and admired, while things like

"The Family" will have returned to the oblivion from which they

never should have emerged.'103 The painting will receive international

acclaim at the Venice Biennale in 1956, and be given historical recognition

in Cinquante Ans d'Art Moderne, held to be one of the most ambitious

attempts to trace and

categorise the development of painting and sculpture from Cézanne

and Rodin to date (World Fair, Brussels, 1958). Le Brocquy's A Family will eventually return from Italy some fifty years later to be displayed

in the National Gallery of Ireland. Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch will

observe on this occasion: 'Le Brocquy is the only living artist to have

a work on show as part of the permanent collection. As Medb Ruane has pointed

out, the prophet has finally been honoured in his own land.'104 This outcome

will not come without further trials and tribulations in the painting's

history. Anne Madden recounts: [In 1966] 'After lengthy negotiations, A

Family [coll. Prealpina S.P.A., Milan] was borrowed for the le Brocquy

retrospective exhibition from the Nestlé Prealpina collection in

Milan. It travelled by boat and was delivered from the Dublin quays to

the Municipal Gallery just in time for the opening of the exhibition. On

opening it, water sluiced out onto the floor of the Gallery ... The artist

was advised, as was a Mr Bull, conservator to the Tate Gallery, London.

After careful examination, Mr Bull pronounced portions of the painting

irreparable and he returned to London ... another expert, John Fitzmaurice

Mills, volunteered to effect restoration. In a few days, he phoned Louis

to say the work was completed. Louis was astonished as he walked through

the door of the appointed room in the Municipal Gallery. There was the

painting, as fresh as before. But as he approached it, his heart sank.

The paint was a caricature of itself. He said not a word but, perceiving

his reserve, Fitzmaurice Mills assured Louis that the paint applied by

him had been diluted with retouching varnish, and was thus removable. Removed

it was ... arrangements were made for the shipment to France. In the meantime,

the painting was placed alone in a room for its safe-keeping. A house painter

entered the room, and fell over an unseen bucket full of white distemper,

spattering it over the surface of A Family, while projecting the

ladder he was carrying through the canvas. Since Louis was not restoring

but repainting the work freely, a difference is perceptible, the older

painter imparting additional vigour to the injured passages which are none

the less integrated within the whole painting. Apart from inadvertent assault,

A Family had now survived both official rejection and prolonged immersion.'105

NEXT

91 John Russell, 'Introduction', Dorothy Walker, Louis

le Brocquy (Dublin: Ward River Press 1981; London: Hodder & Stoughton

1982), p. 9.

92 John Berger, 'Distinguished Humility', Art News and Review (London.

June 16, 1951).

93 Dr. Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch, 'Louis le Brocquy's A Family :

"An unwholesome and satanic distortion of natural beauty" CIRCA

Art Magazine (online magazine, 2002).

94 Louis le Brocquy, 'A Family', Address on the occasion of the installation

of the painting in the collection o the National Gallery of Ireland (Dublin,

May 27, 2002).

95 John Berger, 'Distinguished Humility', Art News and Review (London.

June 16, 1951).

96 Alistair Smith, 'Louis le Brocquy: On the Spiritual in Art', exhibition

catalogue Louis le Brocquy, Paintings 1939 - 1996, (Dublin: Irish

Museum of Modern Art, October 1996 - February 1997), p. 33.

97 Harriet Cooke, 'Harriet Cooke Talks to Louis le Brocquy', The Irish

Times (Dublin, 25 May 1973).

98 Statement made to the editor, August 2005.

99 Eric Newton, 'Round the London Art Galleries', The Listener (London,

June 14, 1951).

100 John Ryan, 'The Louis le Brocquy Exhibition', Our Nation (Dublin,

January 1952).

100b Victor Waddington suggests to the Friends of the National Collections in Ireland (FNCI) to purchase the painting for the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art (now Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane). FNCI/03/03. Box 16, National Irish Visual Art Library archives.

101 "Verdad", 'The Family', letter to the editor, The Irish

Times (Dublin, March 6, 1952).

102 M.A.T., Dublin Evening Mail (March 13, 1952).

103 'Tomtom", 'Paintings of "The Moderns", letter to the

editor, Dublin Evening Mail (March 20, 1952).

104 Dr. Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch, 'Louis le Brocquy's A Family :

"An unwholesome and satanic distortion of natural beauty" CIRCA

Art Magazine (online magazine, 2002).

105 Anne Madden le Brocquy, Louis le Brocquy: A Painter Seeing his Way (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1994), pp. 167-68.

|

A Family, 1951

oil on canvas, 147 x 185 cm

National Gallery of Ireland

Man Writing, 1951

oil on canvas, 62.5 x 76 cm

Merrion Hotel, Dublin

Adam and Eve in the Garden, 1951-52

Aubusson tapestry, 140 x 275 cm

Atelier Tabard Frères et Soeurs, edition 9

Eden, 1952

Aubusson tapestry, 110 x 180 cm

Atelier Tabard Frères et Soeurs, edition 9

Cherub, 1952

Aubusson tapestry, 110 x 140 cm

Atelier Tabard Frères et Soeurs, edition 9

|